Dover-Calais post-Brexit trade plagued by uncertainty

Peter Foster writes in FT today that sIx months before new rules begin there is no clarity on plans to manage cargo traffic.

Standing on the white cliffs of Dover looking down on the ancient port’s modern freight terminal, two truths about the management of the UK trade border after Brexit instantly become apparent.

First, wherever the new customs checks take place after January 1 next year, they cannot be in Dover Port: between the vertical chalk cliffs and the granite harbour wall there is simply no space to build new facilities. Even today the port has fewer than 10 lorry bays for customs checks.

The second inescapable fact is the speed and volume of the traffic that flows continuously from the French coast, clearly visible across the Channel. Even during the Covid-19 crisis Dover has handled about 7,000 trucks a day, but that can reach 10,000 in peak periods.

At present, from the moment a truck drives off the cargo deck of the ferry, it takes less than four minutes to reach the port’s exit and begin its journey onwards into Britain before returning back into the Continent in a constant circular flow.

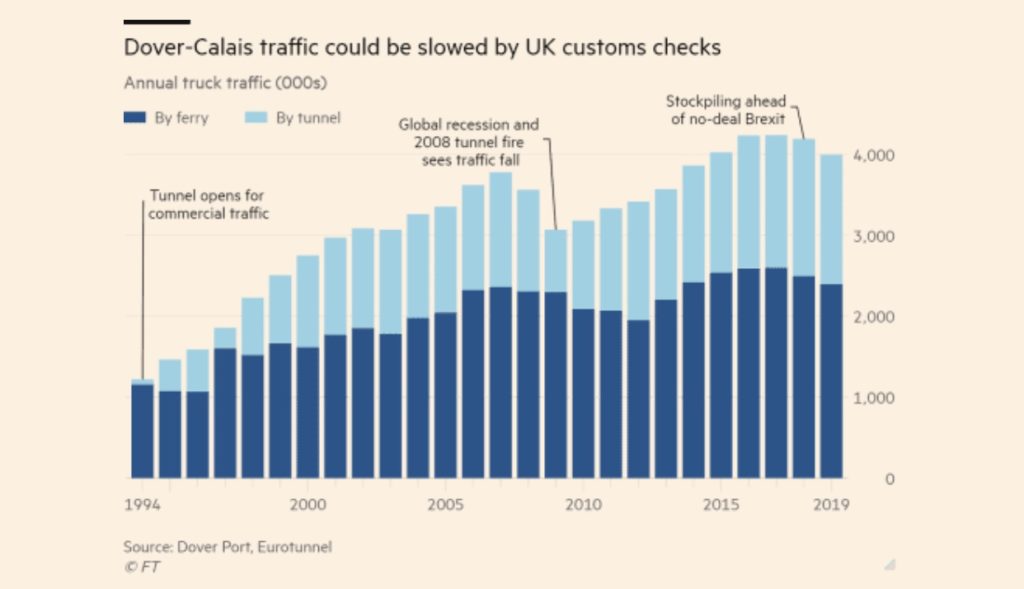

But from January 1 this “roll-on, roll-off” traffic from the EU — totalling about 4m trucks a year when the Channel tunnel is included — is to be subject to full customs controls for the first time. It is estimated that the new system will have to handle up to 200m new declarations a year.

How the government plans to manage the new UK customs border remains unclear because, with less than six months remaining until the new regime comes into force, it has still not published its Border Operating Model.

However it works, the new system will involve a huge step-change, said Tim Reardon the head of EU Exit for Dover Port. At present almost all the freight entering the UK that requires customs controls is “unaccompanied” — it comes in boxes and containers that can sit in docks and airport warehouses until cleared for onward delivery.

“But Dover Port is not a depot, it’s a gateway,” he said, “so we need a border management process that keeps this river of traffic flowing, rather than imposes on lorry traffic the same processes we have on unaccompanied boxes.”

Eurotunnel, which handles 1.5m trucks a year, has the same problem at its site in Folkestone 10 miles west along the coast from Dover, added John Keefe, the director of public affairs at Getlink, the tunnel’s owner. “We just have no space,” he said.

Despite the negotiations on the future relationship appearing to stall in Brussels last week, the UK’s draft Free Trade Agreement does contain a section on facilitating “Ro-Ro” ports with both sides recognising each others’ trucking permits regime to enable free-flowing traffic.

EU officials said the two sides were “not far apart” on key issues, but noted such easements would still require an overall EU-UK deal to be agreed. In a no-deal outcome, the UK would potentially face greater restrictions, including significant shortages of trucking permits when it fell back on to the European Council of Ministers of Transport system.

Ports and haulage industry insiders say the border blueprint was promised to industry in March, then again privately in April and May, but was ultimately delayed by the Covid-19 crisis. Industry now expects it “later this month” but the government declined to confirm a date.

What has been made clear by Michael Gove, the Cabinet Office minister, is that deal or no deal, the UK will not take the laissez-faire approach of previous no-deal plans, which prioritised traffic flows with simplified customs procedures.

In February he announced that a full customs, VAT and regulatory border will be enforced. The UK will also not seek an exemption from Safety and Security declarations for hauliers, adding another 200m separate declarations to the annual tally.

On the French side, a new post-Brexit border system is already in place. Importers and exporters will need to prepare customs documentation that will be converted into a barcode that will marry goods with hauliers at the check-in point for the ferry or train. Trucks without the correct paperwork will not be allowed to board.

During the short journey to France screens in driver lounges will indicate whether trucks will go into an orange lane (for inspection) or a green lane for free onward passage into the EU.

For trucks entering the UK, the system is still unclear. Given the physical space constraints at the port, the expectation from operators is that checks will be conducted at inspection zones away from the port, or in the warehouses where goods arrive.

Among the potential sites under discussion are the Ashford truck park and the existing customs park at the Stop 24 services, both 15-20 miles up the M20 motorway from Dover. Industry has also suggested building further customs examinations centres around the country to avoid potential traffic bottlenecks on the south coast.

Businesses with “authorised economic operator” status are expected to be able to complete formalities at the factory or warehouse where goods arrive and depart, but just slightly more than 1,000 of the estimated 150,000 UK businesses completing customs formalities for the first time after Brexit have AEO status. How much flexibility they will enjoy is unclear.

Ultimately the biggest concern, said Richard Burnett, the chief executive of the Road Haulage Association, is that even if checks are pushed away from the ports to keep the trucks rolling, this will only work if business has the correct papers.

Mr Reardon, of Dover Port, said the market should drive compliance. Since UK exporters will need to have exported their goods properly in order to claim their VAT refund and their EU customers will need to have imported them correctly in order to place them on the market, there is a built-in incentive to get the paperwork right.

But Mr Burnett is sceptical. “If you are a business grappling with this for the first time and you don’t have the right paperwork, are you going to stop trading — or will you take a risk and head to the port?” he said.

Last week Mr Burnett, whose association in March petitioned the government to extend the Brexit transition period, wrote again to ministers warning there was just “too little time” for hauliers and their customers to prepare for the new border.

“We are still missing the essential practical information on all new processes and procedures for importing and exporting goods to ensure fluidity at the border,” he said in a letter to Penny Mordaunt, the paymaster general.

Mr Keefe at Getlink concluded that preparing traders was by far the biggest problem confronting government and industry as they continued to wrestle with the fallout from the coronavirus crisis.

“The sudden change in administrative burden from ‘you don’t have to do anything’ today to ‘you may have to do everything’ is huge,” he said. “There is a great deal of uncertainty and little time to sort it out.”

A government spokesperson said that business would “need to prepare” for life outside the customs union and single market at the end of 2020. “We continue to develop our systems in readiness for the end of the transition period and we are engaging with industry as plans develop,” they added.

Source: FT

You must be logged in to post a comment.