A new Tory initiative to improve border security was launched today.

The Conservatives are publishing plans to improve the UK’s border security after Brexit.

If the party wins the general election, it says it will introduce automated exit and entrance checks. It would also make it harder for people with serious criminal convictions to enter the UK from EU countries.

Labour says the UK would no longer have access to EU databases or the European Arrest Warrant, undermining the fight against terror and organised crime.

Announcing the Conservatives’ plan, Home Secretary Priti Patel said: “When people voted to leave in 2016, they were voting to take back control of our borders. “After Brexit we will introduce an Australian-style points based immigration system and take steps to strengthen our border and improve the security of the UK.”

The party says introducing automated entry and exit checks and a requirement for biometric passports will enable to the government to “know who and how many people are in the country, and to identify individuals who have breached the terms of their visa and restrict illegal immigration”.

Visitors to the UK from the European Union and the Commonwealth will have to comply with a US-style electronic visa system after Brexit.

The plans for a new Electronic Travel Authorisation system (ETA) will make it easier for border guards to screen arrivals and block threats from entering the UK, the Tories say.

It is part of a five-strong plan to secure the borders after Brexit and will be launched by Ms Patel and Boris Johnson, the Prime Minister, at a border post today.

Other measures include plans to count visitors into and out of the UK and to stop migrants using EU identity cards instead of the more secure passports.

New powers will also be brought in to stop EU criminals at the border once the UK has left the EU and ended free movement of people. The renewed focus on immigration comes amid alarm in the Tory party about a tightening in Mr Johnson’s lead in the polls.

Controlling immigration is seen as one of the areas where the Tories are strongest over Labour.

Source: BBC and Telegraph

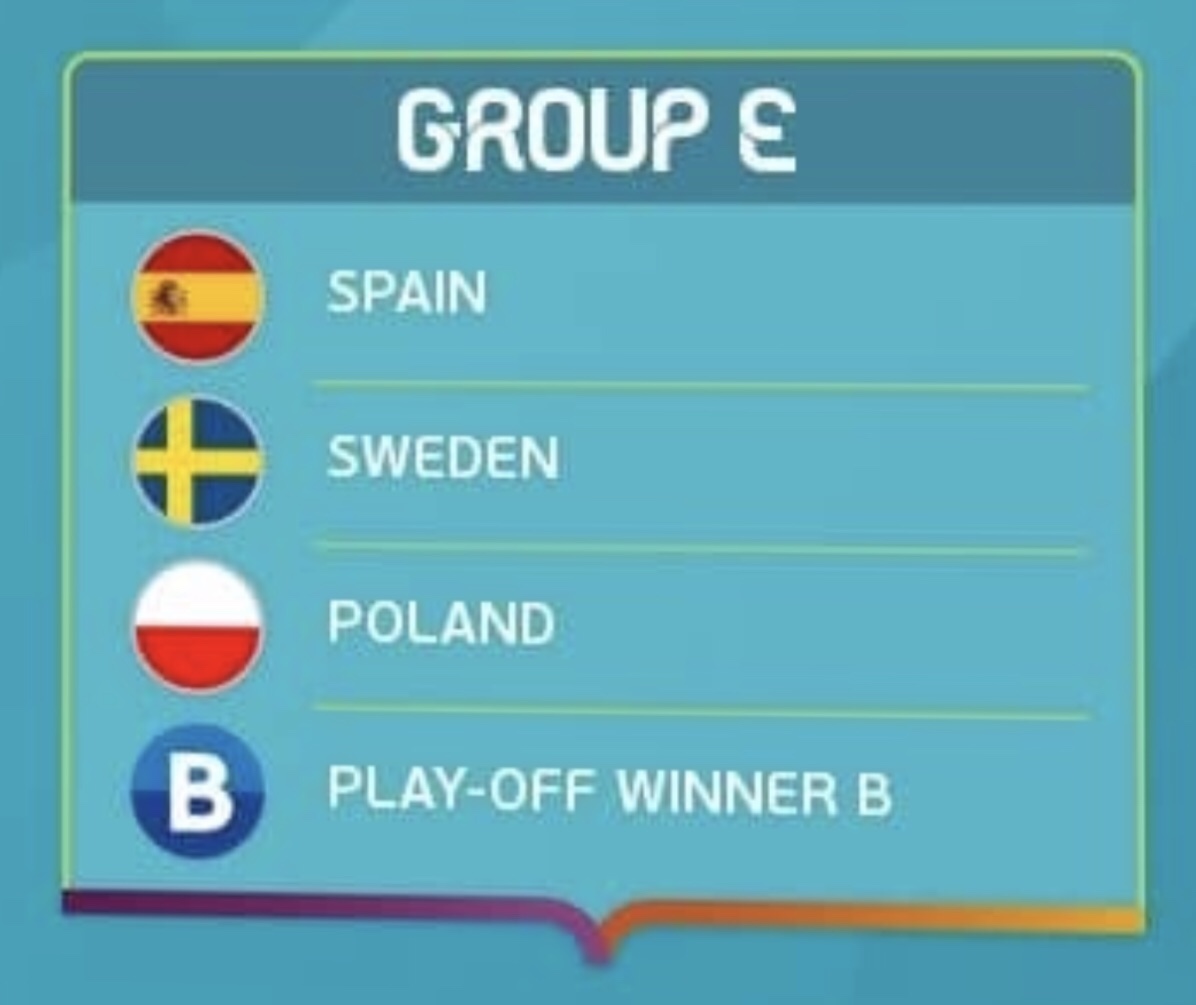

The draw for the UEFA EURO 2020 final tournament took place in Bucharest yesterday.

The tournament will open in Rome at 21:00 CET on 12 June. The group stage runs, with up to four matches a day, until 24 June (last matches in each group played simultaneously).

Sweden will play Spain and Poland in the group round with one ganenin Zargosa and two ganes in Dublin.

The final and fourth group member is decided in a play-offs in April 2020. On our group we will get the winner of; Bosnia and Hercegovina, Northern Ireland, Republic of Ireland and Slovakia.

The most interesting group was without a doubt, Group F with European Champions Portugal, World Champions France and Germany. This is what experts call a group of death.

We have an interesting new young team. We have with this team beaten Italy, France, Mexico and played draws against Spain and Netherlands.

It will be another great football summer 2020.

Conservative MEP and journalist Daniel Hannan wrote an interesting article about Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and a potential new FTA with Japan.

Even though some elements are not considered in the article, like agriculture, and the references to the Treasury calculations might be somewhat too strong – but I think the article is very interesting and bring a perspective on trade deals that is worth noting.

Here is the article:

Let’s remind ourselves why we are leaving the EU. The past three-and-a-half years have seen both sides entrench, like soldiers in the blasted mud of Flanders. Leavers accuse Remainers of betraying democracy. Remainers retort that the referendum was illegitimate, ill-informed and ill-gotten. Each side fires ordnance across no-man’s land, having all but forgotten why the conflict began.

Well, I haven’t forgotten. Brexit, for me, is about two things. First, democratic self-government: the supremacy of our own law. Second, global Britain: our ability to pursue our own foreign policy and trade deals without Brussels intermediaries.

The potential value of this second is illustrated in a paper by two international trade experts, Deborah Elms and Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, A Better Fit: Remodelling the EU-Japan EPA After Brexit, published yesterday [SAT] by the Initiative for Free Trade (of which, to declare my interest, I am President). Japan is the world’s third economy, and has traditionally seen Britain as its key partner. Around a thousand Japanese firms invest in the UK, employing, according to the Japanese government, 97,000 people.

Before we come to the benefits of a trade deal, it is worth noting that, of all the biased reports put out by Treasury Europhiles – all those duff predictions of rocketing unemployment and falling stock prices and housing collapses – the silliest has to do with trade. The Treasury solemnly claims that leaving the EU’s customs union would lower our GDP by 7.5 per cent whereas the gain of doing trade deals with the rest of the world would be equivalent to just 0.2 per cent of GDP.

What? What? The EU accounts for 44 per cent of our exports – a number falling by the week. So how can those two figures both be true? In order to come up with its numbers, the Treasury made a series of absurd assumptions: that Britain would impose tariffs on EU imports (we announced ages ago that we would do no such thing); that our trade deals with the US and others would be no more ambitious than what Brussels was proposing; that we would replicate, rather than improving, the deals with third countries that we inherited from the EU.

Why should we be so lacking in ambition? The EU-Japan deal, which entered into force this year, is limited in scope. EU negotiators were mindful of Continental agrarian and industrial interests, not British services. The authors of today’s report calculate that the total gain to the UK is less than 60 per cent of the average gain to the EU.

Happily, the Japanese government doesn’t want to “roll over” the existing EU deal with Britain. It aims higher, especially in investment, financial services and digital trade. Since these are precisely the areas where Britain stands to gain, we should grab the offer.

One of the saddest things about the past three years has been our timidity. Our civil servants approached Brexit in a spirit of damage-limitation. Our trade officials, for all that ministers claimed otherwise, assumed that we were staying in the EU’s customs union, even if under another name.

Things changed only when Boris arrived in Downing Street. Liz Truss, our dynamic new trade secretary, wants 80 per cent of our trade to be covered by FTAs within three years. We are exploring state-of-the-art agreements with allies like Japan, providing for mutual recognition in services, non-discrimination in investment, cross-border data flows and easier movement for service providers.

These things define modern trade. The arguments about agricultural standards and tariffs on manufactured goods, so important in Brussels, belong to a past century.

There is a strong case for prioritising Japan – along with Australia, New Zealand and Singapore. Britain should apply, in parallel, to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which brings together those countries and seven other Pacific states.

True, we are not a Pacific nation (except in the technical sense of owning Pitcairn), but we have exceptional links with the region – not just to Australia, New Zealand and Canada, but to other common-law states such as Malaysia. The geographical determinism that lay behind the European project in the 1950s has been overtaken by technology.

These days, cultural proximity trumps physical proximity. We start from a position of unique regulatory inter-operability with several of the CPTPP members – although we have lately been dragged into the EU orbit on issues like digital commerce.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Britain stood consciously aside from the European alliance system – a policy later known as “splendid isolation”. Our one alliance, after 1902, was with Japan, the mirror island monarchy at the other end of the Eurasian landmass. The thinking was that our interests could not clash – and, indeed, Japan loyally supported us through the Great War. Only later, as Japanese rivalries with the United States rose, did our treaty lapse.

Japan, like Britain, is an old country that looks across the oceans for its prosperity. We are natural partners. ‘Tis a consummation devoutly to be wished.

Source: Telegraph

You must be logged in to post a comment.