I have had two days of very good meetings in London.

KGH is expanding and we are setting up a large operstion in Unitef Kingdom right now.

We are also involved in the BREXIT development work, both with Government and the Private Sector.

I will be in London a lot this year. I like the city.

Today I have been in Athens for meetings. It is always great to visit Greece. Arrived yesterday.

It is some time since I was here last. Havibg said that, good to see old friends and potential new partners – and to dicuss how to save the world. Again.

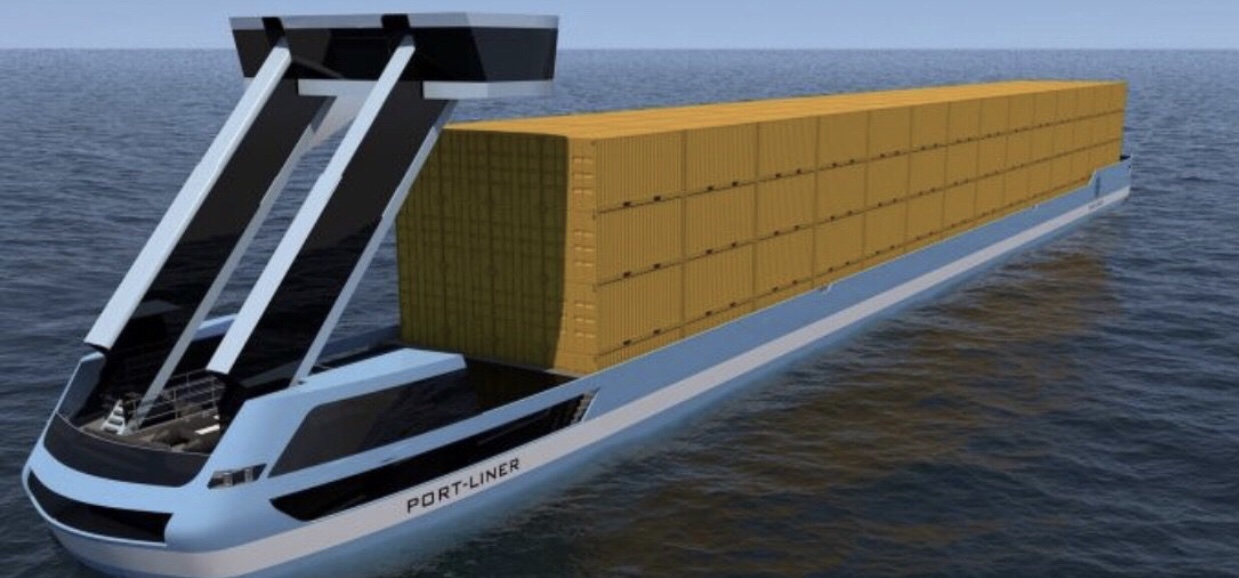

The Dutch company Port-Liner is building two giant all-electric barges dubbed the ‘Tesla Ships’. The company announced that the vessels will be ready by this autumn and will be inaugurated by sailing the Wilhelmina canal in the Netherlands.

The battery-powered barges – pictured above – are capable of carrying 280 containers.

The first 6 barges are expected to remove 23,000 trucks from the roads annually in the Netherlands and replace them with zero-emission transport.

Port-Liner is developing its own vessels, but they developed a battery pack technology that houses the batteries inside a container.

You must be logged in to post a comment.