Apple Incs publicly traded worth just put it in never-before-seen territory: the world’s first $1 trillion company.

The financial benchmark was reached Thursday, 42 years after Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak and Ronald Wayne founded the Apple Computer Company in Los Atlos, Calif.

Apple shares were up 22 percent so far this year.

Swedish international pop star Robyn has annpunced that she will release a new album later this year. This will be her first new music since the albums Body Talk 1-3 in 2010. The albums had numerous hit singles including ‘Dancing on my own’.

Robyn is already back with the single “Missing u” released on Wednesday this week and in addition, the Swedish star of BBC Radio 1 revealed that her next album is ready and will be released this year.

The new album is primarily recorded in Robyn’s own studio in Stockholm, and she thinks she has a sensuality and softness that has not been in her music before.

“When I wrote this album, I was quite tired of writing sad love songs … but I did it anyway,” she told the radio channel.

In addition to the upcoming album, fans can also look forward to an upcoming documentary.

British police and armed forces could be guaranteed uninterrupted access to the encrypted signal of the European Unions Galileo satellite system, it has emerged, as Brussels negotiators consider a unique deal for the UK on the project after Brexit.

The EU’s chief Brexit negotiator, Michel Barnier, is mulling an offer on the satellite project that would put the UK on better terms than other third-party countries over use of the encrypted service, according to diplomatic sources.

The plans, which are still on the drawing board, suggest a bit more flexibility than Barnier’s public position that the UK would be tretaed like any other non-EU country.

But in a blow to the government, the EU has not budged in its insistence that UK-based firms should be excluded from building modules for the secure signal,

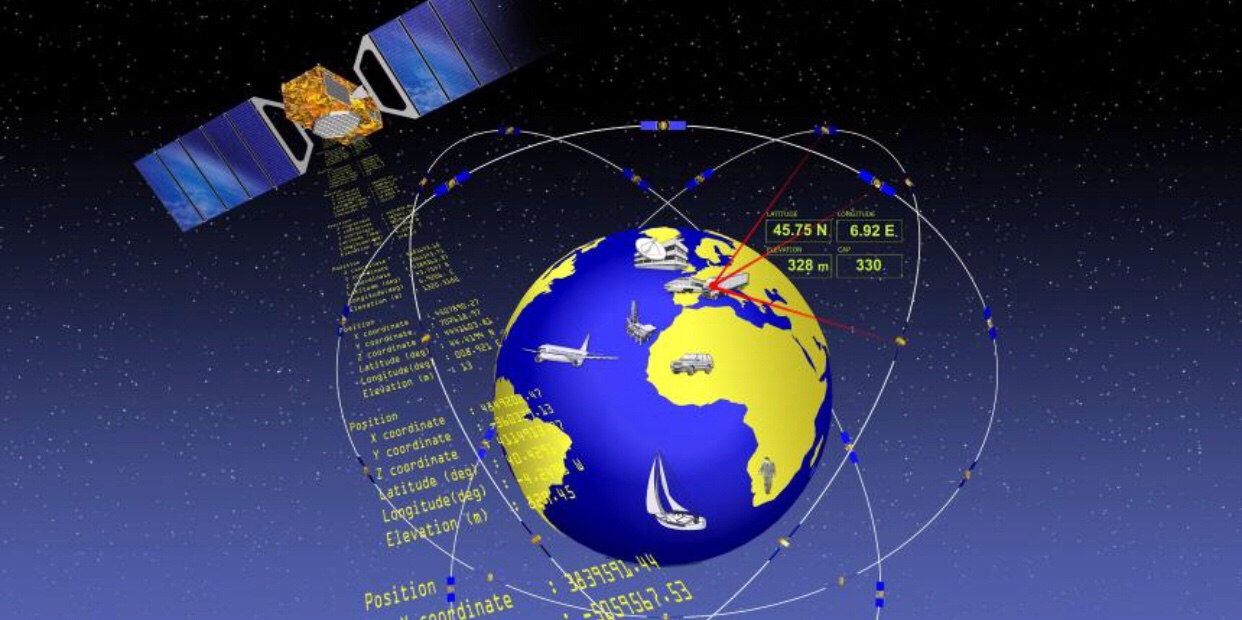

Conceived as the EU’s answer to the US global positioning system (GPS) and Russia’s global navigation and satellite system (Glonass), the €9.7bn (£8.6bn) Galileo project now has 26 satellites orbiting the globe, providing free global positioning to smartphone companies, app developers and search and rescue services anywhere in the world.

At the heart of the Brexit clash is Galileo’s public regulated service (PRS), the encrypted signal that cannot be jammed by hostile powers. The PRS can be used by governments during national emergencies, such as terrorist attacks, and allows the military to plan operations and guide missiles. Barnier has said he wants a partnership with the UK over the “most sensitive signal”, but it now emerges the commission could go a step further.

At a closed-door meeting last month, the commission floated the idea of involving British officials in decision-making over any restrictions on the PRS. “To me this is not heresy, this is the logical consequences of a close partnership on security,” said one source.

Another official said the UK could be offered a guarantee not to be “cut off in any circumstances”, albeit stressing none of the ideas had been agreed among EU member states.

The UK was once sceptical about Galileo, which used to be referred to in British official circles using the uncomplimentary term “the common agricultural policy in space”. Having spent £1.2bn on Galileo, the UK wants to ensure access on the same terms after Brexit to prevent British-based space companies moving operations to the continent.

The government has said that UK-based firms must have the right to “compete fairly for PRS-related contracts” and has threatened to walk away from Galileo and build its own satellite system unless this demand is met.

Source: The Guardian

You must be logged in to post a comment.