EU negotiators are ready to offer Theresa May a free-trade area after Brexit but say that, contrary to her “Chequers” plan, there must be a customs border that will make trade less than “frictionless”, according to an internal EU document seen by Reuters on Tuesday.

The document — three pages of “defensive points” for EU officials to make against the UK prime minister’s July proposal on future ties with the bloc — may offer May some comfort in showing a readiness to seal a free trade agreement (FTA) like those giving access to Japan or Canada’s goods and services.

But as she prepares for her Conservative Party conference this weekend, it also rams home, in some detail, the rejection of the Chequers proposal for a special customs deal that would avoid border checks on goods and keep supply chains fluid.

Brussels argues it would give Britain an unfair advantage in the single market, applying some EU rules but not others.

Apparently taken aback by the latest EU rejection of that idea when she met fellow leaders at a summit in Salzburg last week, May has insisted she is sticking with the plan, despite fierce opposition from some in her party. She complained that the EU had not given her detailed reasons for its rebuff.

The document, sent to EU governments on Friday morning as British media declared Salzburg a major setback for May, does go into detail, which officials said EU negotiator Michel Barnier had given to the 27 leaders over a lunch on Thursday.

British officials had, well before Salzburg, been briefing opposing arguments to Barnier’s. But EU officials and diplomats said all leaders had given support to their negotiator. One said they understood that the customs element of May’s Chequers plan would damage their own economic interests.

Another EU official said May had not only irritated leaders by insisting vocally and very publicly that there was no alternative to her idea but by saying the EU objections had not been given to British negotiators in detail.

Reflecting comments made since July by Barnier, the document lays out EU officials’ thinking on Chequers, named after May’s residence where the plan was hammered out.

It concludes it would “give the UK an unfair competitive advantage” — while also saying officials “welcome … proposals to develop an ambitious new partnership” for which the Chequers proposal of a “free trade area” should be “the starting point”.

Britain’s goods could only get unfettered access to the EU’s market if the UK remains “fully bound by the EU acquis (accumulated legislation) in the same way as other single market members, including supervision and enforcement”.

Since Britain has firmly ruled that out, saying it will leave the EU’s single market and the customs union, the document says a Canada-style FTA is the only remaining option.

“An FTA cannot ensure entirely ‘frictionless’ trade,” the document says, adding there must be a customs border between the EU and Britain after Brexit.

“As a result, the UK’s goods trade will over time be less closely integrated economically with the EU than it is now. For example, cross-border supply chains will not operate seamlessly.”

May’s “common rulebook” for goods would give Britain unfair advantage, it says. In one example, studies showed that most of the regulatory costs for steel or chemicals producers were not in product standards, which Britain offers to meet, but in standards for production methods — such as rules on pollution — from which London wants to be able to diverge.

It said British producers would have to conform to EU rules to be allowed into the single market: “This will make the biggest difference for agriculture and sensitive industrial goods with authorisations by public bodies including chemicals, automotive, pharmaceuticals, biocides.”

It also explains EU concerns that “embedded services”, such as the financing of car sales, represent much of the cost of many goods and that, under Chequers, Britain offers to match EU standards only on the final product, not rules that apply to, say, how workers produce the services that accompany them.

The document also provides officials with an argument to counter British complaints that Brussels has offered to keep Northern Ireland effectively inside its economic rulebook in order to avoid border infrastructure with EU member Ireland that both sides fear could revive conflict on the island.

The issue, the document spells out, is that with 1.8 million people and “unique circumstances”, the EU is willing to make a special case of Northern Ireland, which is “much less of a competitive threat than the 60-million UK”.

May again stressed on Tuesday that Britain needs to see EU counter-proposals to move the Brexit negotiations forward.

Adding to May’s Brexit woes on Tuesday, Britain’s main opposition Labour Party signalled it would vote against any deal she clinches with the EU and would be open to a second referendum with the option of staying in the bloc.

Source: Reuters

“Time is running out! We’re expecting a stormy autumn: industrial and trade companies, as well as the asset management industry, must now seek to make the necessary arrangements with their financial services providers. It is important to Brexit-proof their financing and investments. That does not work at the touch of a button. We’re heading for a mass start which will lead to a bottleneck for those late to the line,” says Hubertus Väth.

Deutsches Aktieninstitut calls upon the European and British negotiating parties to finally place their trade relations on a new sustainable basis. In its third position paper on the Brexit negotiations Deutsches Aktieninstitut shows using as examples tariffs and product approval as well as derivatives and data protection that companies cannot solve all the problems arising due to Brexit on their own.

The position paper can be downloaded here.

Visit the KGH Brexit Symposoum in Soest on 20-21 November learn everything about the result from the Extra EU Brexit Summit to be held second week of November. Still a few places left.

What will be the outcome of the withdrawel negotiations, a deal or no-deal? Either way, what does the outcome mean in practice on the ground. Come and find out.

Albanian outfits have pushed out rivals by slashing the price of the drug.

Albanian gangsters have taken control of the UK’s cocaine market by imitating the “Amazon model” of using efficiency gains to offer high-quality products at the lowest possible price.

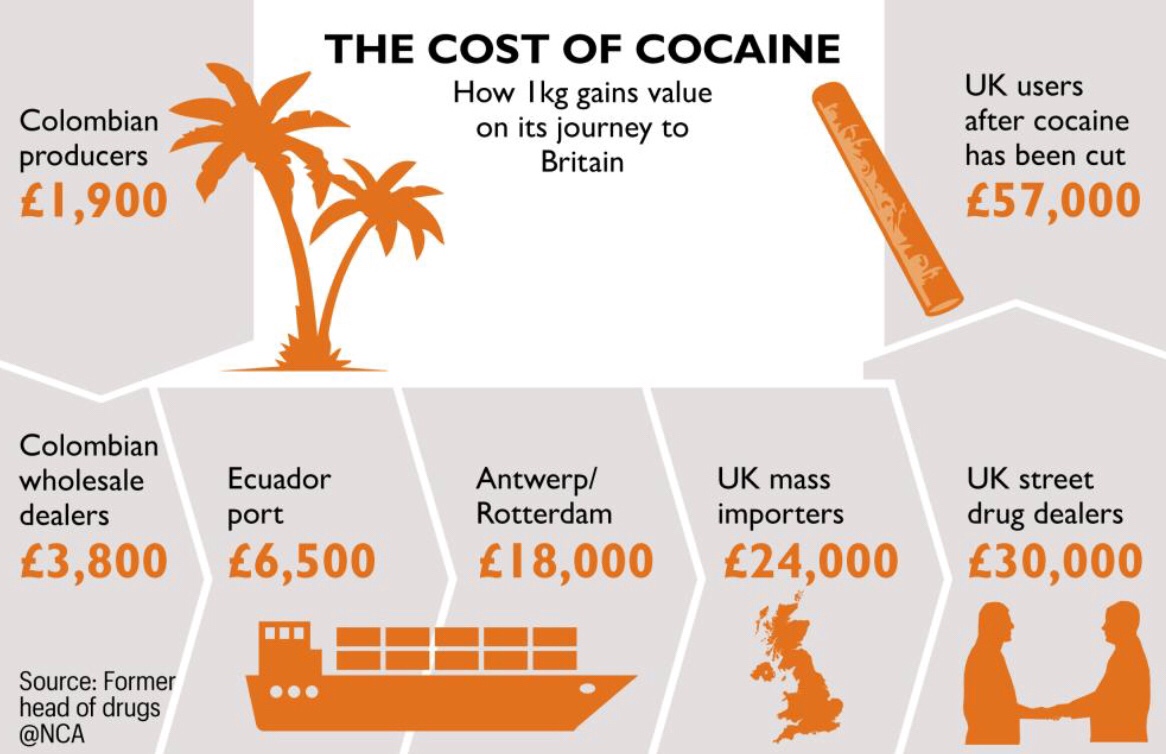

Tony Saggers, former head of drugs at the National Crime Agency (NCA), said the extraordinary success of Balkan criminals in Britain meant that the price of cocaine had been slashed by a third — to £30,000 a kilo — in five years.

At a conference earlier this month the former senior law enforcement official said Albanians had managed to undercut drug trafficking rivals by forging direct relationships in Latin America, the region where most of the world’s cocaine is produced from indigenous coca leaves.

One kilo of cocaine can be bought for as little as £3,800 in the jungles of Colombia and sold for almost £60,000 in Britain once it has been mixed with cutting agents and divided into grams.

Saggers said the eastern Europeans’ grip on the UK drugs market had made them leading figures in the underworld and allowed them to compete with traditionally powerful domestic organised crime syndicates.

“I don’t think there is another commodity on the planet that generates that sort of difference between production and retail value,” he said. “The Albanians are controlling cocaine from Latin America all the way into our marketplace.”

The news that the price of cocaine has slumped will raise fresh fears over the impact of the drug on British society. The Sunday Times revealed in June that a Home Office report blamed the recent rise in murders and robberies on cocaine flooding into the country.

Last week the inquest into the death of socialite Daisy Boyd, 28, heard that she had sent pictures of herself snorting cocaine to another patient hours before she killed herself in a private psychiatric hospital in London.

Saggers, who retired from the NCA last year, explained how Albanians had come to dominate the UK underworld. He said organised crime syndicates had moved into western Europe after the refugee crisis caused by the war in Kosovo between 1998 and 1999.

“The Kosovo crisis generated a lot of movement. Many Albanian criminals took advantage of that, pretended to be Kosovans and moved to Europe,” he said.

“They established themselves, sometimes with new identities but certainly with residency status. And they did that for criminal gain. They saw the opportunity.”

Saggers added that the Albanian people’s struggles under communism — a regime that ruled the country from the end of the second world war until 1992 — had prepared them for the tough world of international drugs trafficking.

“They have gone through instability and had to fight for survival. Smuggling became an important part of Albanian culture when they were part of the communist regime. They are very good smugglers,” he said.

“They came here under the guise of fleeing conflict and set up efficient, amicable business models, but with an underlying emphasis [to rivals] of: we don’t want to fall out with you . . . but trust us, you want to fall out with us less.

“They have a long-term approach to success. They have got rich slowly. They now dominate drugs market prices by selling at the lowest price. They don’t impact upon purity by adulterating it — they make relationships upstream and establish staging posts through Europe and they have done everything in a slow, efficient, sustainable way.

“If they weren’t doing what they are doing, you’d take your hat off to them and say this is a fantastic business model.”

Key to the Albanians’ success in the UK, according to Saggers, is their ability to deal directly with people in Latin America. He said the price of the drug escalates as it is carried from Colombian jungles via South American ports across the Atlantic to the European ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam, both cocaine transit hubs, where it is sent on for sale on the streets of Britain.

“Every single stage comes with risk,” said Saggers. “And the more people that are involved in the risk heightens the likelihood that people in the supply chain would be exposed.

“Wherever you buy from and your position in the supply chain will determine the price you pay. The really successful drug traffickers are the ones that can go straight into Latin America and control the activity all the way to the UK.”

Saggers said the Albanians were so successful that they had “individually and systematically brought the price down from over £45,000 a kilo five years ago to about £30,000 a kilo now”.

The number of patients admitted to UK hospitals suffering from cocaine- related “mental disorders” has more than doubled in the past 10 years.

In 2007-8, 5,148 patients were admitted to hospital suffering from “mental and behavioural disorders due to use of cocaine”. By 2016-17 the figure had risen to more than 12,000, according to figures from NHS Digital.

Last year Britons consumed 30 tons of the drug — more than any other country in Europe and up by 40% in 20 years. Despite this, the NCA has had some notable successes against Albanian organised criminals.

Khalad Uddin, 35, described as the “kingpin” in an elaborate drug-dealing UK network, was jailed for 16 years in June last year. Olsi Beheluli, an actor and model from Albania, was jailed for 15 years for drug dealing after he posted a photograph of himself on Twitter surrounded by £240,000 in cash.

Source: Sunday Times

You must be logged in to post a comment.