A new ranking has revealed which nations have the most powerful passports. Passport Index ranks our travel documents by measuring the number of countries that can be visited without applying for a visa.

The 2016 ranking puts Germany and Sweden at the top of the passport league. Holders of German and Swedish passports can visit 158 countries without the need to apply for a visa.

Last year, the United States and the United Kingdom shared the top spot. The US has now slipped to fourth place.

British passports have slipped to second place, where they enjoy the same status as France, Spain, Switzerland and Finland.

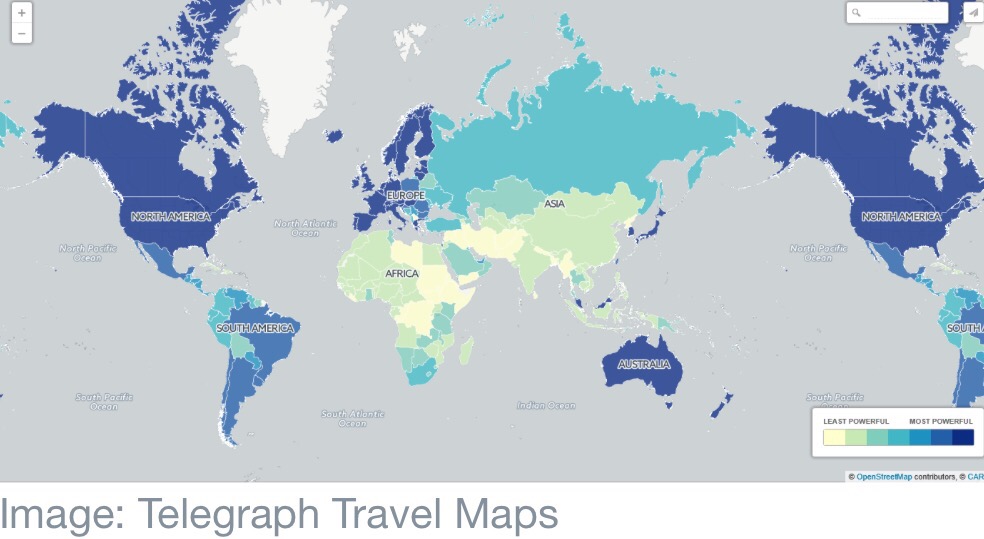

The map below shows the global distribution of the most and least powerful passports.

The least powerful passports are issued by poor countries, often mired in conflict. The people of Afghanistan can only visit 24 countries without applying for a visa. Pakistan fares little better, with just 31 countries offering visa-free travel. The passport of the world’s newest nation, strife-torn South Sudan, only allows visa-free access to 36 countries.

South Africa has the highest-ranking passport in continental Africa. It is placed 46th in the world and grants holders access to 91 countries without the need for a visa.

The African Union has recently launched a trial of a single African passport that allows holders visa-free access to all 54 AU member states.

Initially the passport is only available to African Union heads of state, ministers of Foreign Affairs and the permanent representatives of AU member states based at the headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

The 2016 ranking puts Germany and Sweden at the top of the passport league. Holders of German and Swedish passports can visit 158 countries without the need to apply for a visa.

The AU has plans to abolish visa requirements “for all African citizens and African countries by 2018”, according to the AU’s Agenda 2063. The AU has suggested 2020 as the roll-out date for a single African passport for all citizens.

AU Commission Chairperson, Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, described the single passport initiative as “a steady step toward the objective of creating a strong, prosperous and integrated Africa, driven by its own citizens and capable of taking its rightful place on the world stage.”

Buoyed by investor interest and hopes that the new government will lift the economy out of recession, the Brazilian real has seen gains of almost 24% against the American dollar in the past year.

Other emerging-market currencies have turned in strong performances against the dollar. This Statista chart from 18 October, based on the 30 currencies monitored by the Thomson Reuters Datastream, shows the Russian ruble up 16% and the South African rand up 8.1%.

At the other end of the scale is the Nigerian naira, in crisis after being hit by low oil prices.

The plunge of the British pound, meanwhile, following the Brexit vote, has made it one of the year’s worst-performing currencies.

As of 18 October, the pound’s year-to-date fall against the dollar was 17.3%.

Amid fears of a “hard Brexit”, investors have been shedding sterling. The currency is at a 31-year low against the dollar, and some analysts believe there may be further drops to come.

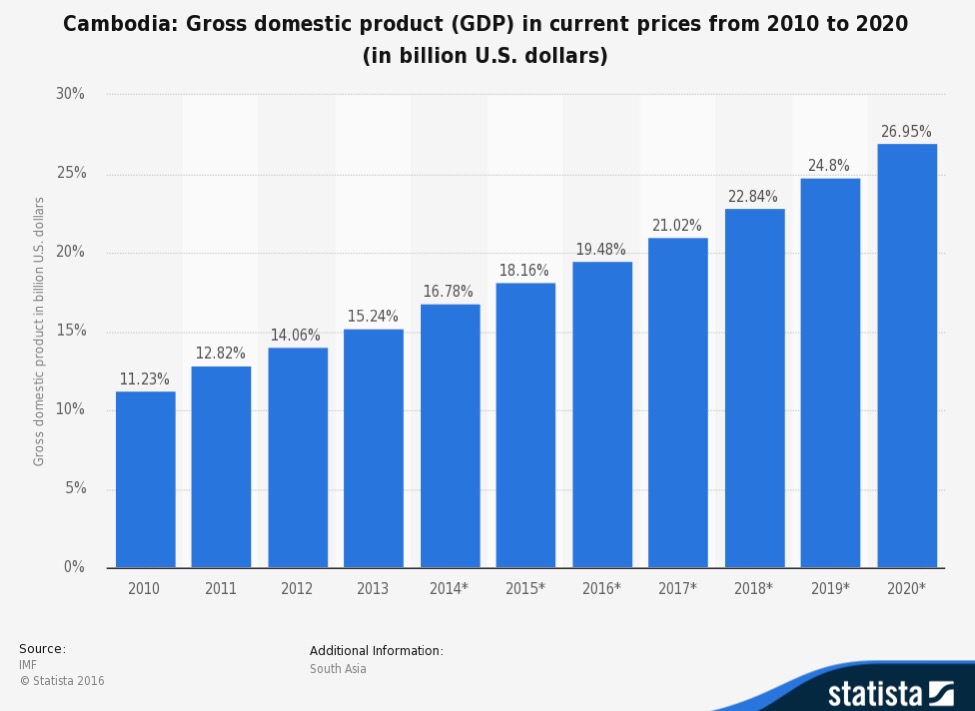

This past summer, the World Bank officially upgraded Cambodia to a “lower‑middle‑income country”, a move that confirms the country’s upwards economic trajectory over the past 20 years.

But despite this new status, which Cambodia shares with 51 other economies, including India, Vietnam and the Philippines, the country is still mostly associated with darker images: landmines, civil war and the Khmer Rouge regime. At best, perhaps, it’s seen as a new frontier destination for investment and tourism.

For development economists, though, this reclassification comes as no surprise: Cambodia’s economic development has earned it the title “olympian of growth” in some quarters, thanks to sustained double-digit growth between the years 1998 and 2015 (with the exception of 2009 and 2010, following the international financial crisis).

This rise is impressive not only for its rate but also for its resilience. The country has been growing at a stable rate over time, making it the world’s sixth-fastest‑growing economy. While some would argue that “it started at a low level, so it’s normal”, the uniqueness of Cambodia’s growth lies in its continuity over 20 years. Since 1950, only 13 economies in the world have grown at a rate above 7% per year for a quarter of a century or longer, and Cambodia is not an oil‑producing country. Its growth has been mostly driven by trade and by a buoyant demand for labour‑intensive manufactures (textiles and clothing), a booming tourism industry, growth in construction and, to a lesser extent, an increase in agricultural exports. New opportunities within the South-East Asian region have also emerged, fuelled by deeper integration in the ASEAN economic bloc.

GDP per capita has increased, inflation has been kept lower than 5% and the poverty rate has declined from 53% in 2004 to 16% in 2013. Yet there’s a long way to go before Cambodia achieves its vision of becoming an upper‑middle‑income nation and meeting all the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 and turning into a developed country by 2050.

Source: WEF

You must be logged in to post a comment.