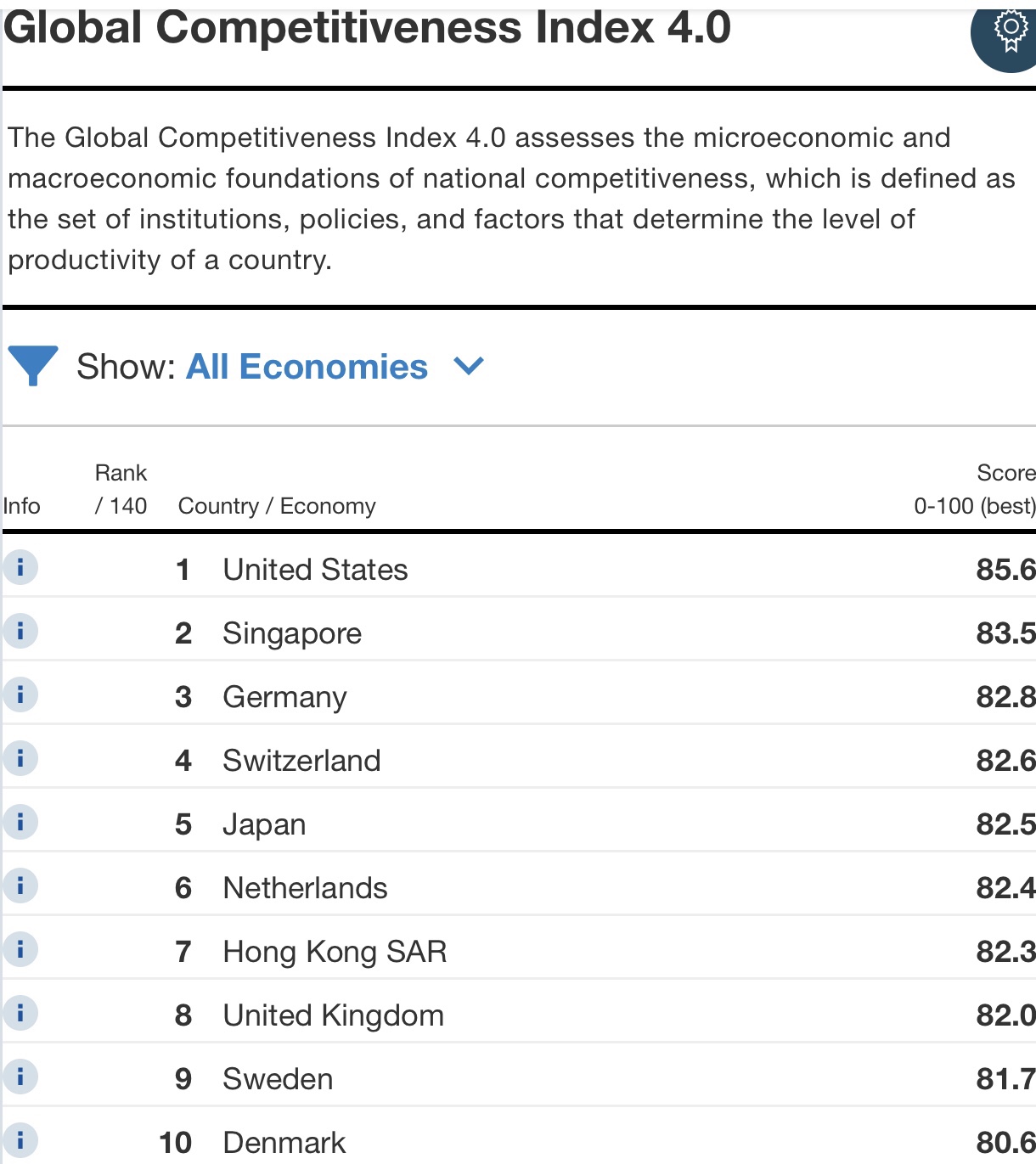

World Economic Forum has released this years’ version of the Global Competitiveness Report measuring contries from several perspectives.

Featuring the new Global Competitiveness Index 4.0, the Report assesses the competitiveness landscape of 140 economies, providing unique insight into the drivers of economic growth in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Discover the 2018 edition’s rankings, key findings, your economy’s scorecard, and much more.

Prime minister seeks to quell growing frustration over EU withdrawal negotiations by highlighting ‘important progress’

Theresa May is to say 95 per cent of the Brexit deal is settled as she seeks to quell mounting frustration at her handling of EU divorce negotiations.

In a Commons statement on Monday following talks with European leaders in Brussels, the prime minister will insist the “shape of the deal across the vast majority” of the withdrawal agreement is now clear.

But she will also reiterate her refusal to compromise over the Irish border, one of the key issues yet to be resolved with just over five months until Britain leaves the EU.

Ms May’s statement to parliament comes as she faces growing anger among Eurosceptic rebels in her own party as well as calls for a second referendum on the final Brexit deal.

In an attempt to highlight “important progress” since a fractious EU summit in Salzburg last month, the prime minister will tell MPs that agreements have been reached on security, transport and services.

She is expected to confirm that protocols have been developed on how Brexit will impact Gibraltar and the UK’s military base in Cyprus.

“Taking all of this together, 95 per cent of the withdrawal agreement and its protocols are now settled,” Ms May will tell the Commons.

“And all of this from the last three weeks alone, is in addition to the agreements we had already reached.

“The commitment to avoiding a hard border is one that this House emphatically endorsed and enshrined in law in the Withdrawal Act earlier this year.

“As I set out last week, the original backstop proposal from the EU was one we could not accept, as it would mean creating a customs border down the Irish Sea and breaking up the integrity of the UK.

“I do not believe that any UK prime minister could ever accept this. And I certainly will not.”

Furious backbenchers warned the prime minister she is “drinking in the last chance saloon” at the weekend after tensions flared over her negotiating strategy after a Brussels summit.

Senior Brexiteer Theresa Villiers criticised “disturbing” anonymous briefings to Sunday newspapers, including claims the PM was entering the “killing zone”.

But Brexit minister Suella Braverman said her colleagues were free to express themselves in any way they wished and repeatedly refused to say she would back Ms May in a confidence vote.

Brexit secretary Dominic Raab said the exit agreement must be finalised by the end of next month to allow new laws to be put in place in time for exit day.

He suggested a transition extension could run for three months, but said the move would have to solve the Irish backstop issue.

Labour has warned Ms May that it will not back her Brexit blueprint when it reaches the Commons.

Shadow Brexit secretary Sir Keir Starmer said there was a real lack of confidence Ms May could bring back “anything by way of a good deal”.

An estimated 670,000 people marched in London on Saturday to demand a second Brexit referendum.

Conservative MP Anna Soubry said many of her Tory colleagues were privately supportive of a fresh vote amid bitter divisions in the party.

Source: The Independent

The Economist writes that EU leaders had once hoped that a provisional Brexit deal would be struck at their October summit, which starts today in Brussels. That would have left enough time for a legal text to be firmed up and sent for ratification to the European and Westminster parliaments before Brexit is due to happen on March 29th 2019. But the timetable is slipping, and there is a growing risk of no deal at all. The main reason is that Theresa May, Britain’s prime minister, has rejected a key part of the EU’s draft withdrawal agreement, a planned backstop to ensure that, no matter what happens to a future trade deal between Britain and the EU, there is no hard border with physical customs controls between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic.

The issue of the Irish border has bedevilled talks from the start. The EU’s guidelines for negotiations, published in March 2017, made it one of three points that needed to be settled in the withdrawal agreement before talks could begin on future trade relations (the other two were settling how much Britain owed for outstanding EU obligations and enshrining the rights of EU citizens in Britain to stay). Last December Mrs May agreed with the EU that, while the intention was to avoid frontier controls through a comprehensive free-trade deal, a backstop solution was needed to ensure no hard border in any circumstances. The problem is that the two sides have different views on how such a backstop should be legally designed.

The EU version would keep Northern Ireland in a customs union and in regulatory alignment with its single market. But Mrs May, strongly pushed by the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), which props up her government, rejects this as it implies that border checks would need to take place between the province and the British mainland. Instead, she proposes to keep the United Kingdom as a whole temporarily in a customs union and in regulatory alignment until technology allows physical border controls to be dispensed with. The EU dislikes the first idea, does not believe technology will ever solve the problem and is against any time limit as it would negate the very purpose of a backstop.

Mrs May still believes a compromise can be found. The EU may after all agree to a backstop that applies to the whole UK. But there is little time left to strike a deal. And what makes compromise most difficult for the prime minister is the risk she faces that the Westminster parliament could say no when she presents it for approval. That could create new uncertainties, including possibly triggering another general election or even a second referendum. With the clock ticking, it could also lead to a disruptive no-deal Brexit next March. The next few weeks will be decisive for the outcome of Brexit—and for Mrs May’s own future.

Source: The Economist

You must be logged in to post a comment.