Cocaine gangs thrive using ‘Amazon model’ marketing

Albanian outfits have pushed out rivals by slashing the price of the drug.

Albanian gangsters have taken control of the UK’s cocaine market by imitating the “Amazon model” of using efficiency gains to offer high-quality products at the lowest possible price.

Tony Saggers, former head of drugs at the National Crime Agency (NCA), said the extraordinary success of Balkan criminals in Britain meant that the price of cocaine had been slashed by a third — to £30,000 a kilo — in five years.

At a conference earlier this month the former senior law enforcement official said Albanians had managed to undercut drug trafficking rivals by forging direct relationships in Latin America, the region where most of the world’s cocaine is produced from indigenous coca leaves.

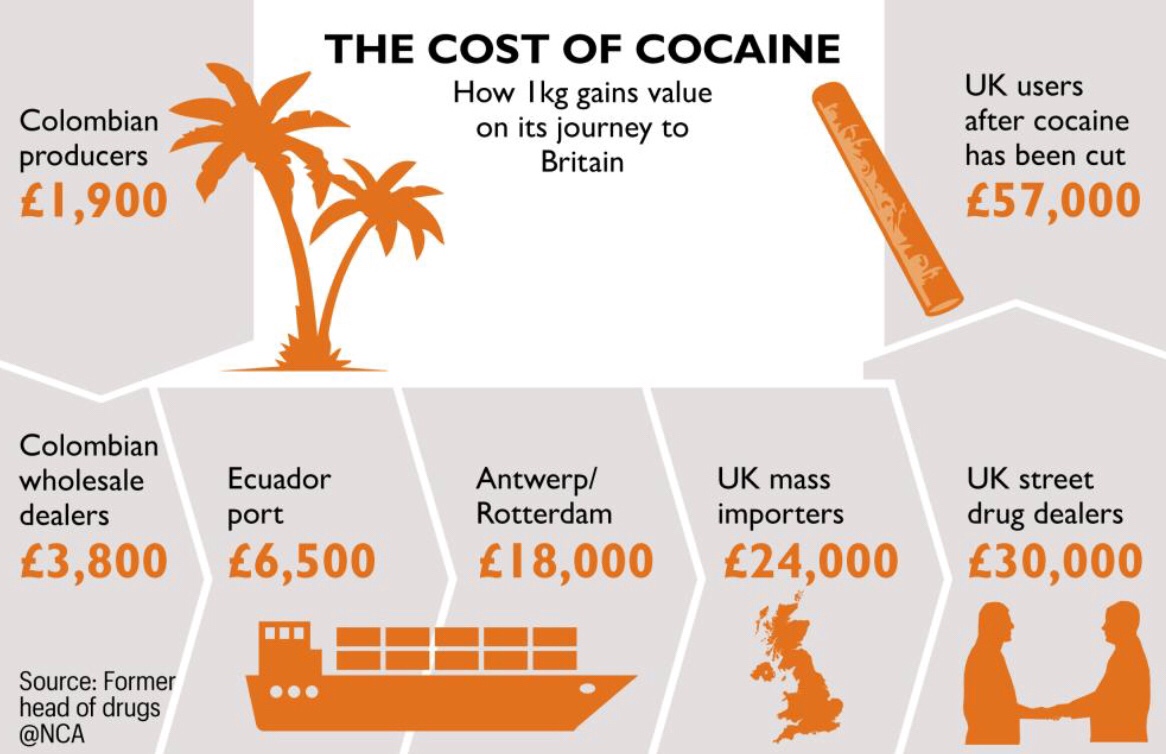

One kilo of cocaine can be bought for as little as £3,800 in the jungles of Colombia and sold for almost £60,000 in Britain once it has been mixed with cutting agents and divided into grams.

Saggers said the eastern Europeans’ grip on the UK drugs market had made them leading figures in the underworld and allowed them to compete with traditionally powerful domestic organised crime syndicates.

“I don’t think there is another commodity on the planet that generates that sort of difference between production and retail value,” he said. “The Albanians are controlling cocaine from Latin America all the way into our marketplace.”

The news that the price of cocaine has slumped will raise fresh fears over the impact of the drug on British society. The Sunday Times revealed in June that a Home Office report blamed the recent rise in murders and robberies on cocaine flooding into the country.

Last week the inquest into the death of socialite Daisy Boyd, 28, heard that she had sent pictures of herself snorting cocaine to another patient hours before she killed herself in a private psychiatric hospital in London.

Saggers, who retired from the NCA last year, explained how Albanians had come to dominate the UK underworld. He said organised crime syndicates had moved into western Europe after the refugee crisis caused by the war in Kosovo between 1998 and 1999.

“The Kosovo crisis generated a lot of movement. Many Albanian criminals took advantage of that, pretended to be Kosovans and moved to Europe,” he said.

“They established themselves, sometimes with new identities but certainly with residency status. And they did that for criminal gain. They saw the opportunity.”

Saggers added that the Albanian people’s struggles under communism — a regime that ruled the country from the end of the second world war until 1992 — had prepared them for the tough world of international drugs trafficking.

“They have gone through instability and had to fight for survival. Smuggling became an important part of Albanian culture when they were part of the communist regime. They are very good smugglers,” he said.

“They came here under the guise of fleeing conflict and set up efficient, amicable business models, but with an underlying emphasis [to rivals] of: we don’t want to fall out with you . . . but trust us, you want to fall out with us less.

“They have a long-term approach to success. They have got rich slowly. They now dominate drugs market prices by selling at the lowest price. They don’t impact upon purity by adulterating it — they make relationships upstream and establish staging posts through Europe and they have done everything in a slow, efficient, sustainable way.

“If they weren’t doing what they are doing, you’d take your hat off to them and say this is a fantastic business model.”

Key to the Albanians’ success in the UK, according to Saggers, is their ability to deal directly with people in Latin America. He said the price of the drug escalates as it is carried from Colombian jungles via South American ports across the Atlantic to the European ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam, both cocaine transit hubs, where it is sent on for sale on the streets of Britain.

“Every single stage comes with risk,” said Saggers. “And the more people that are involved in the risk heightens the likelihood that people in the supply chain would be exposed.

“Wherever you buy from and your position in the supply chain will determine the price you pay. The really successful drug traffickers are the ones that can go straight into Latin America and control the activity all the way to the UK.”

Saggers said the Albanians were so successful that they had “individually and systematically brought the price down from over £45,000 a kilo five years ago to about £30,000 a kilo now”.

The number of patients admitted to UK hospitals suffering from cocaine- related “mental disorders” has more than doubled in the past 10 years.

In 2007-8, 5,148 patients were admitted to hospital suffering from “mental and behavioural disorders due to use of cocaine”. By 2016-17 the figure had risen to more than 12,000, according to figures from NHS Digital.

Last year Britons consumed 30 tons of the drug — more than any other country in Europe and up by 40% in 20 years. Despite this, the NCA has had some notable successes against Albanian organised criminals.

Khalad Uddin, 35, described as the “kingpin” in an elaborate drug-dealing UK network, was jailed for 16 years in June last year. Olsi Beheluli, an actor and model from Albania, was jailed for 15 years for drug dealing after he posted a photograph of himself on Twitter surrounded by £240,000 in cash.

Source: Sunday Times

You must be logged in to post a comment.