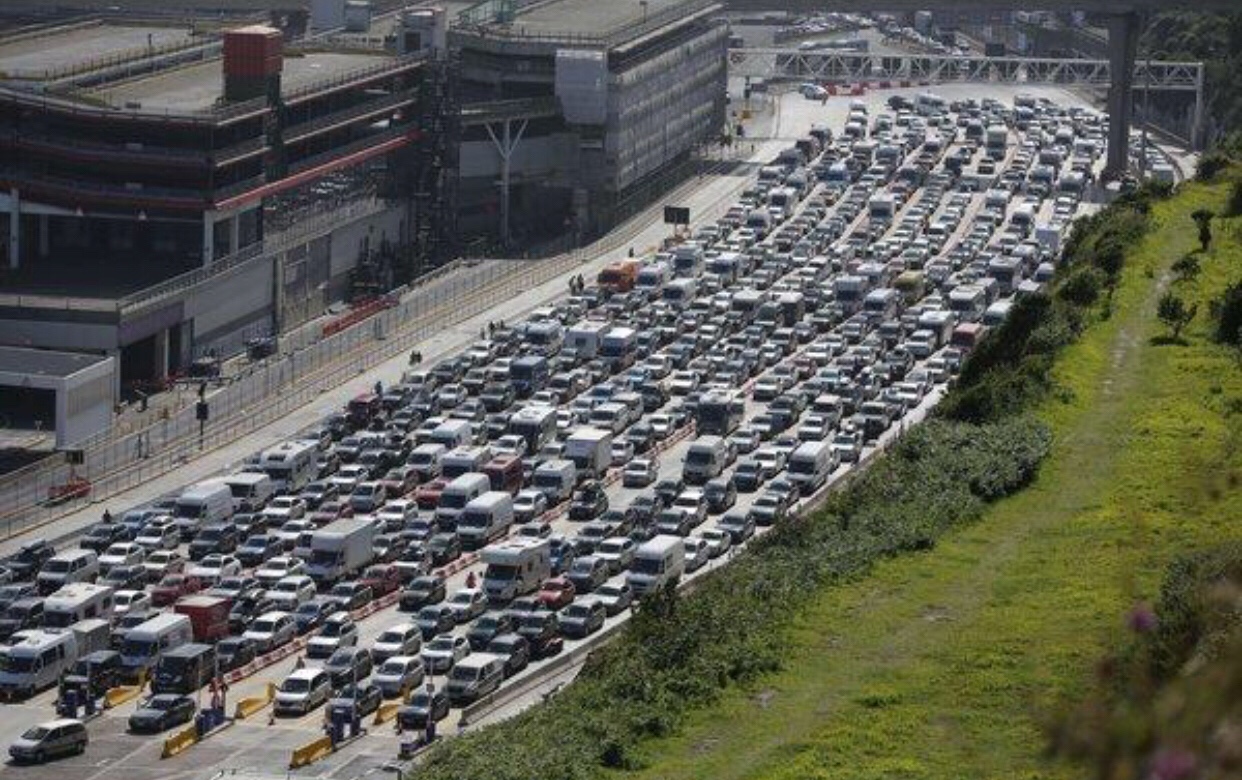

Brexit Nightmare: 17-Mile Traffic Jams at the Dover Border

How dors the rest of the world look st Brexit and what is now the challenges in the negotiations between UK and EU?

This article from the New York Times. Wrotten by Stephen Castle show one of the views.

“Trucks rumble nonstop through Britain’s busiest ferry port, one every few minutes, some headed for France, others arriving here in Dover, where they trundle along an elevated roadway that scales the town’s striking white cliffs.

But a cloud is hanging over the ceaseless flow of cargo to and from continental Europe — and it is more than a fog blown in from the English Channel.

Of the thousands of trucks that use Dover each day, only a fraction are stopped by British officials. That is because both Britain and France are members of the European Union and of its customs union, which removes the need for border checks on most goods.

Yet when Britain quits the bloc, a process known as Brexit, all that could change, and the question of how, when — or whether — to abandon a European customs union has divided and paralyzed the British cabinet.

Most attention has ficused on the border between Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom, and Ireland, which will remain in the European Union. But for Britain’s economy, Dover matters much more.

So vicious is the political infighting over what might happen here that there is talk of a snap general election, or a leadership challenge against Prime Minister Theresa May from her party’s restive, hard-line pro-Brexit faction, whose cheerleader, the lawmaker Jacob Rees-Mogg, has accused her government of “abject weakness.”

Passions are inflamed because Brexit supporters see leaving the customs union as “a totemic embodiment of what it actually means to leave the European Union,” said Simon Fraser, a former head of Britain’s foreign office, now managing partner at Flint Global, a consultancy.

“They see the risk that Britain will leave the European Union legally, but stay within a customs union and so remain bound by European Union trading rules,” Mr. Fraser added.

Those who want to keep close ties to the bloc point to warnings that quitting a customs union could cause chaos at ports and cost firms more than $25 billion a year.

Certainly, Mrs. May could pay a high political price if she gets things wrong.

Here at Dover, within eight minutes, trucks can normally disembark, move out of the port and onto the highway — where most pass a Brexit-inspired mural by Banksy, depicting a worker chipping away at a star on the European Union flag.

Only around 2 percent of trucks carry goods from outside the European Union. Those require a customs clearance, but that is done at separate centers away from the port and can take anywhere from 20 minutes to several days, said Richard Christian, head of policy and communications at the Port of Dover.

In the absence of the customs union, every single truck would, in theory, be subject to such a close examination. Yet, even a modest, two-minute delay in processing truck arrivals could cause a 17-mile line of traffic, says Mr. Christian. He recalled disruption along those lines following strikes that brought gridlock, leaving trucks waiting for hours on highways outside the port and on the other side of the English Channel in France.

“There were supermarket shelves empty and cars not being built; we know what happens when traffic can’t move across the channel,” he said.

Officially, Mrs. May is committed to quitting Europe’s customs union because continued membership would prevent Britain from striking independent trade deals — a primary selling point of the Brexiteers.

She favors a “customs partnership” under which Britain would collect tariffs for the European Union on many goods but would be able to strike some separate trade agreements. Though complex, this would keep Britain close to many economic rules and strictures of its biggest trading partner.

For that reason it infuriates hard-line Brexit supporters who want to break free and detach Britain from the orbit of Brussels.

Brexiteers prefer another plan called “max fac” — short for maximum facilitation — that accepts the need for customs controls but uses technology to keep checks light.

One recent report pro-Brexit report [the Longworth/Cambell-Banner report – that BTW refers to my report on SmartBorders2.0, my comment] called for national borders to become “less of a physical location, and more of a digital record,” with import and export transactions rooted through an online portal.

Seen from Dover, the outline of a workable replacement for a customs union that can process the huge volume of cross-channel trade looks less visible than the French coast on a misty day.

After decades of European integration, companies assume they can move goods freely across frontiers; components are shipped so that they arrive “just in time” to go on auto factory assembly lines without storage, and pharmaceuticals and food also need to arrive fast.

The number of trucks using Dover has increased by 150 percent since 1993, when Europe’s economic integration accelerated, with more than 2.5 million passing through the port every year, according to the institute for Government, a research group.

“Goods worth $159 billion passed through the port in 2015, representing around 17 percent of the UK’s entire trade in goods by value,” it said.

Were all trucks to face customs checks — rather than the current 2 percent — there would be no space for them in Dover’s port, Mr. Christian says.

“All the land is reclaimed, we have the famous white cliffs behind, we have sea and breakwaters in front and we have a town to the side,” he added.

Building customs points or truck parks outside the port would take time and money, but until decisions about the customs union are made, nothing can be done.

“We need to know now what we need to deliver,” Mr. Christian said. “We need to know as soon as humanly possible.”

Source: New York Times

You must be logged in to post a comment.