Brexit: What is the ‘no-deal’ Australia option?

Remember how this time last year we were talking about a no-deal Brexit? Well, it’s back.

It is not exactly the same thing, because the UK left the European Union (EU) on 31 January.

The UK is now in a transition period with the EU until 31 December 2020, which means it is still following EU rules and trade stays the same. The transition was meant to give both sides a bit of time to negotiate a future trade agreement.

But if there is no trade deal by the end of the year, the UK would automatically fall back on World Trade Organization (WTO) rules.

The government now refers to this no-deal outcome as an “Australia-style deal” (Australia trades with the EU largely on WTO rules).

Boris Johnson said on 16 October: “we should get ready for January 1 with arrangements that are more like Australia’s”.

The WTO is the place where countries negotiate the rules of international trade – there are 164 members and if they don’t have free-trade agreements with each other, they trade under basic “WTO rules”.

Every member has a list of tariffs (taxes on imports of goods) and quotas (limits on the number of goods) that they apply to other countries with which they don’t have a deal. These are known as WTO schedules.

How does trade with the EU work now?

The EU is the UK’s biggest single trading partner. In 2019, it accounted for:

43% of UK exports

51% of UK imports

As an EU member, the UK was part of its trading system – the customs union and the single market. This meant there were no tariffs on goods traded between the two, and minimal border checks.

This arrangement continues until the end of the transition period.

And both sides are trying to reach a new free-trade agreement – one without tariffs or quotas – before then.

What happens if there’s no trade deal?

The UK would have to trade with the EU on WTO rules – at least, initially.

In this scenario, the EU would impose its tariffs on imported UK goods.

The average EU tariff is pretty low (about 2.8% for non-agricultural products) but in some sectors tariffs can be quite high.

Cars would be taxed at 10% with some agricultural tariffs higher still – rising to an average of more than 35% for dairy products.

This would have a big impact on UK businesses selling their goods to the EU.

It has already released details of the tariffs it will charge from January 2021 to countries with which it does not have a free trade deal.

In some areas, they will be imposed to protect UK producers – in the car sector, for example, and on most agricultural products, to avoid “additional disruption for UK farmers and consumers”. That will lead to higher prices in the UK for some EU goods.

But the government is also removing some of the tariffs it has been charging as part of the EU – in areas, for example, where there isn’t that much domestic UK production that needs protecting.

It means that 47% of all imported products will have zero tariffs, compared with 27% when in the EU. Imported yeast, for example, will have its tariff cut from up to 14.7% to zero. That will lead to lower prices in the UK for some goods.

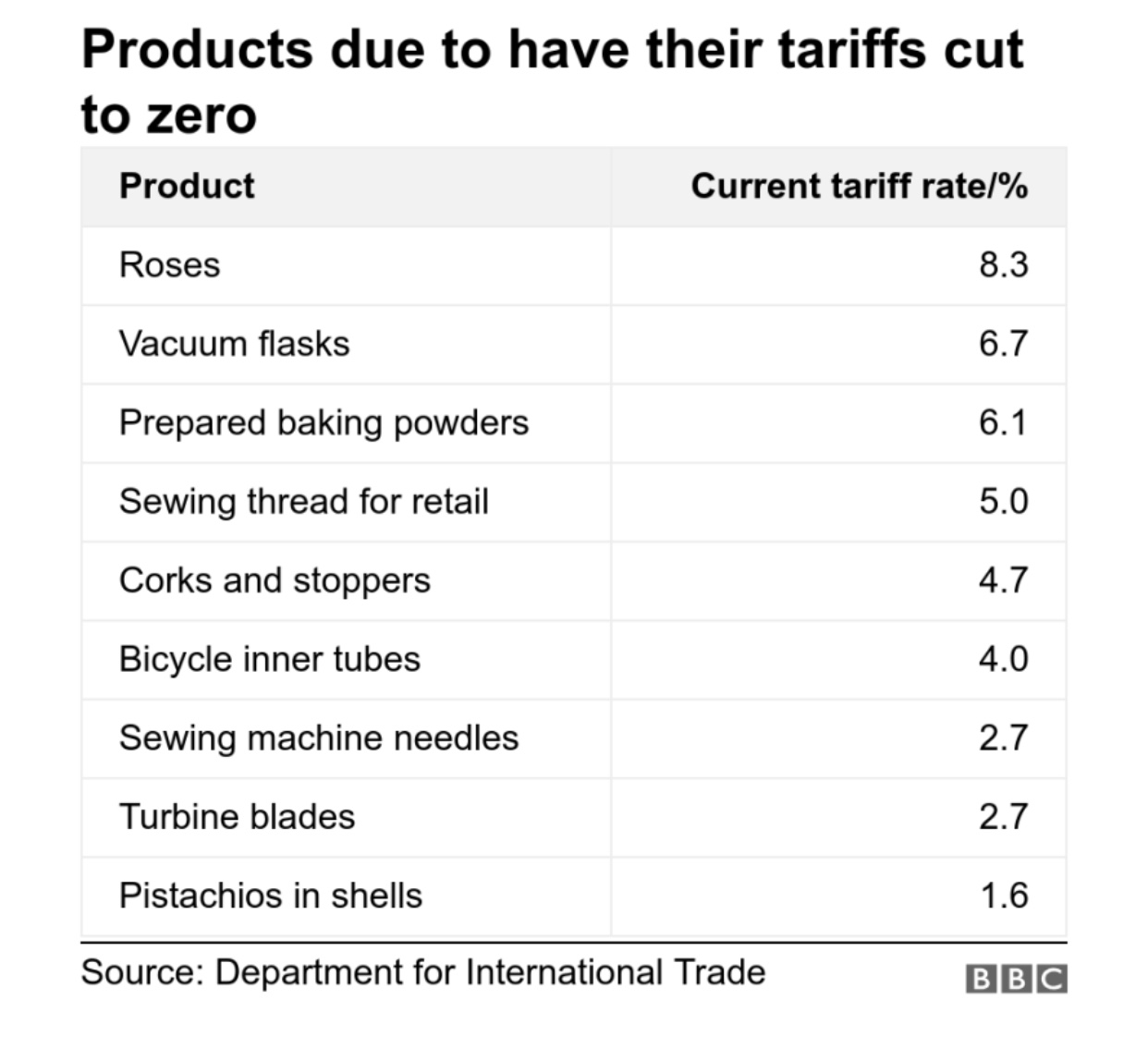

Here are some other items that are having their tariffs cut to zero.

At first glance it looks like trade overall would be freer, but it wouldn’t be to begin with.

Don’t forget that the EU is the UK’s biggest single trading partner, and at the moment there are no tariffs at all on UK-EU trade.

Without a deal before the end of this year, that will all change.

It’s also important to remember that the WTO’s “most favoured nation” rules limit room for manoeuvre in the event of no deal.

The UK couldn’t for example lower tariffs for the EU alone, in order to keep trade going. It would have to treat the rest of the world in the same way, which could lead to cheap imports flooding the UK economy, and harming domestic businesses.

And it’s not just about the tariffs – there are also what are called “non-tariff barriers”, which include things like product standards, safety regulations and sanitary checks on food and animals. Without a trade deal all of these things will have to be checked at borders, leading to lengthy delays.

And eventually, negotiations on some kind of deal would have to begin again.

All of this refers only to the trade in goods.

The trade in services between the UK and the EU is also of critical importance. The kind of trade deal the two sides have been trying to negotiate wouldn’t say very much about services anyway. But no deal would be an even greater challenge for service industries.

Don’t other countries trade with the EU on WTO rules?

Yes, examples include the United States and China, Brazil and Australia.

In fact, it’s any country with which the EU has not signed a free-trade deal. That’s when WTO rules kick in.

But it’s a lot more complicated than that. Those big economies don’t just rely on basic WTO rules – they have all done other deals with the EU on top of that, to help facilitate trade.

The US, for example, has at least 20 agreements with the EU that help regulate specific sectors, covering everything from wine and bananas to insurance and energy-efficiency labelling.

Australia also has such agreements, including a 2008 deal that made it easier for Australian wine to access European markets.

An “Australia-style deal” is being talked about by the government – it would mean the UK trading with the EU in roughly the same way Australia does. But it amounts to the same thing as leaving without any trade deal and trading on WTO rules.

And it’s important to consider geography.

Australia is on the other side of the world, whereas the UK is the EU’s next-door neighbour. That means Australia doesn’t rely on the EU in the way the UK does, for the operation of just-in-time supply chains in sectors such as cars, pharmaceuticals and food.

So border checks and delays have far less impact on EU-Australia trade than they would on EU-UK trade.

In other words, going to WTO rules for trade with the EU – without any other deals in place – would be a huge change.

And companies on both sides would be having to adjust to that change at the same time as trying to deal with the impact of coronavirus.

Source: BBC

You must be logged in to post a comment.